Cyber archeology: a new way to explore the past

Cyber archeology: a new way to explore the past

In 1870, when the archeologist Heinrich Schliemann found the city of Troy, his main working tools were spoons, knives, pickaxes and a few tons of dynamite

Almost a century and a half after this finding, archeologists around the world carry out their excavations using much more modern equipment: drones, scanners, high resolution cameras and devices that capture 360 degree and 3D images.

Technologies existing only in science fiction books until not long ago now help us to better understand our past.

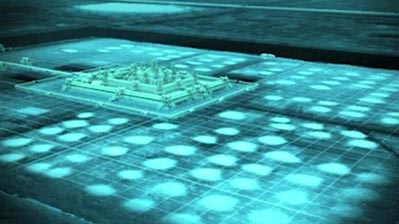

One of the main tools used by cyber archeologists – archeologists who use technology to perform their work – is the LIDAR, or Light Detection and Ranging (something like Detection and Mapping by Light). These devices work with laser pulses and are normally coupled to airplanes or drones to fly over a determined site scanning its topography. The accuracy is such that they can “see” details like the distance and form of objects.

Right after, they take the collected data to the laboratory and reassemble in virtual reality the images obtained. All without having to dig an inch of the ground. The detailed virtual representation makes the identification of what is earth, stone or archeological material easy, preserving the soil and its layers of superimposed history.

At the beginning of last year, this technology helped an international team of scientists to make a great discovery in the Aguada Fenix region, in Mexico. A setting of dense vegetation and difficult access.

After flying over the site with a drone equipped with a LIDAR scanner, the images obtained by the equipment revealed a platform 1.4 km long, built over three thousand years ago with clay and dirt. The largest and oldest monument of the Mayan civilization found so far: a carefully prepared artificial platform to allow the observation of the rising Sun at the beginning of the summer and the winter as well as to study the movement of the stars. These are hypotheses raised by the scientists who participated in the research.

Recently other archeological discoveries were made possible by this technology.

An Italian group of cyber archeologists mapped the Roman city of Falerii Novi, founded over two thousand years ago and completely buried. With no excavation, just using this modern equipment, a temple, a theatre and an underground plumbing network were found.

Another scientific expedition discovered almost a thousand new archeological sites on the Scottish island of Arran. Among the relics found at the site were prehistoric settlements and medieval farms.

In Cambodia, images captured by a drone equipped with LIDAR revealed a lost medieval city approximately 1,200 years old.

In Dourado, a Brazilian city located 280 km from Sao Paulo, engineering students discovered an archeological site over 12,600 years old full of rupestrian inscriptions never reported before.

All of this technology has enabled scientists to exchange studies and research between laboratories around the world quickly and safely, and has expanded the range of researchers willing to analyze the terrain and identify more points of interest. Many web surfers who carry the spirit of researchers within them, can also analyze the images collected in search of still unknown archeological treasures, through the platform GlobalXplorer (www.globalxplorer.org).

In the last few years man has made great technological advances. But, the more they move towards the future, the greater seems to be their willingness to know the past, who they are, and where they came from. With the help of technology, cyber archeologists aim to answer at least part of these questions. Only time will tell if they will make it.

Collaboration: André de São Plácido Brandão