A Linen Cloth and Its Stories

A Linen Cloth and Its Stories

Biblical accounts state that the body of Jesus, after His crucifixion, was carefully wrapped in linen cloths, according to the custom of the time and the Jewish tradition. Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin and a respected counselor, reportedly approached Pilate with the intention of offering Jesus a dignified burial:

“When (Joseph of Arimathea) had taken the body, he wrapped it in a clean linen cloth, and laid it in his new tomb which he had hewn out of the rock; and he rolled a large stone against the door of the tomb, and departed.” (Mt 27:59–60)

“Then they (Joseph and Nicodemus) took the body of Jesus, and bound it in strips of linen with the spices, as the custom of the Jews is to bury. Now in the place where He was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb in which no one had yet been laid. So there they laid Jesus, because of the Jews’ Preparation Day, for the tomb was nearby. “ (Jn 19:40–42)

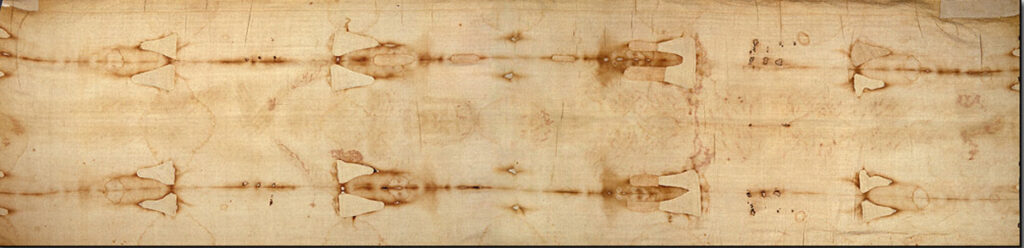

Centuries later, the so-called “Shroud of Turin” — a linen cloth measuring 1.10 m wide by 4.36 m long — kept in the Cathedral of the Italian city, began to attract millions of visitors interested in contemplating the image of a human body imprinted on the fabric. The visible marks appear consistent with injuries typical of someone who had been scourged and crucified. Forensic studies indicate that the visible wounds align with Roman crucifixion practices from the first century. Another relevant point is the presence of pollen from plants native to the region of Palestine, along with the type of cotton fiber used in the fabric — both elements common to textile production in that region of the Middle East.

Could this be the same linen sheet that wrapped the body of Jesus? How could it have reached the Cathedral of Turin? And what do the studies say about its composition and dating?

Many questions surround the history of the Holy Shroud. The search for answers has sparked debates among historians, theologians, archaeologists, chemists, biologists, and researchers from various universities around the world. Since the earliest examinations, a definitive consensus still seems far off.

One hypothesis suggests that the Shroud was taken to the city of Edessa (now Urfa, in Turkey) by disciples of Christ, seeking protection from persecution. About 500 years later, it is said to have been rediscovered, well-preserved, and hidden within a city wall. In 944, it was transported to Constantinople and, in 1204, taken by crusaders from Western Europe. From 1346, the Shroud came to be associated with the name of Count Geoffroi de Charny (*1). Centuries later, it was moved from Chambéry, from the collegiate church of Lirey (about 150 km from Paris), to the Cathedral of Turin, as a fulfillment of a vow by Saint Charles Borromeo.

In light of growing scientific interest, the cloth underwent various analyses, which identified that the markings do not contain any traces of paint or organic pigments. One of the most accepted hypotheses suggests that the image, formed from monochromatic shades, resulted from fiber dehydration caused by intense radiation of heat or light. Studies conducted in 1973, analyzing different light intensities, revealed a three-dimensional aspect of the image.

Year after year, many questions remain unanswered. Although carbon-14 dating analyses (an archaeological technique used to estimate the age of carbon-containing objects) yield divergent results regarding the exact date, it is still unclear what technique generated the image. Despite technological advances, no scientific experiment has managed to precisely reproduce the process that created the image on the Shroud. The absence of traditional pigments challenges the hypothesis that it was painted (*2).

In 2022, researchers from the Institute of Crystallography in Italy (*3) conducted new dating analyses of the cloth using X-ray technology. Their results suggest that the materials that make up the Shroud of Turin are compatible with the time period in which Jesus is believed to have lived. Recently, images recreated by artificial intelligence, based on the face printed on the Shroud, exhibit characteristics similar to traditional depictions of Jesus in visual art.

Some see the Shroud as material evidence of Jesus’ resurrection. Others investigate what physical phenomena might have suddenly released an energy burst powerful enough to mark the cloth — and withstand time.

Although the research remains inconclusive, the story of the linen cloth that, according to tradition, wrapped the body of Jesus of Nazareth continues to be an invitation for reflection. The meanings of renewal and transformation associated with Easter have deeply marked the history of Western civilization. Contemplating the journey of the Shroud and its symbolism of “passage” is an opportunity for reflection — not only for science, but for all those interested in this story and its millennia-long influence.

Footnotes

(*1) Espinosa, 2024, p. 12

(*2) Espinosa, 2024, p. 86

(*3) De Caro et al., 2022

References

ESPINOSA, Jaime. O Santo Sudário. São Paulo: Quadrante, 2024.

DE CARO, Liberato; SIBILLANO, Teresa; LASSANDRO, Rocco; GIANNINI, Cinzia; FANTI, Giulio. X-ray dating of a Turin Shroud’s linen sample. Heritage, v. 5, n. 2, p. 860–870, 2022. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5020047.