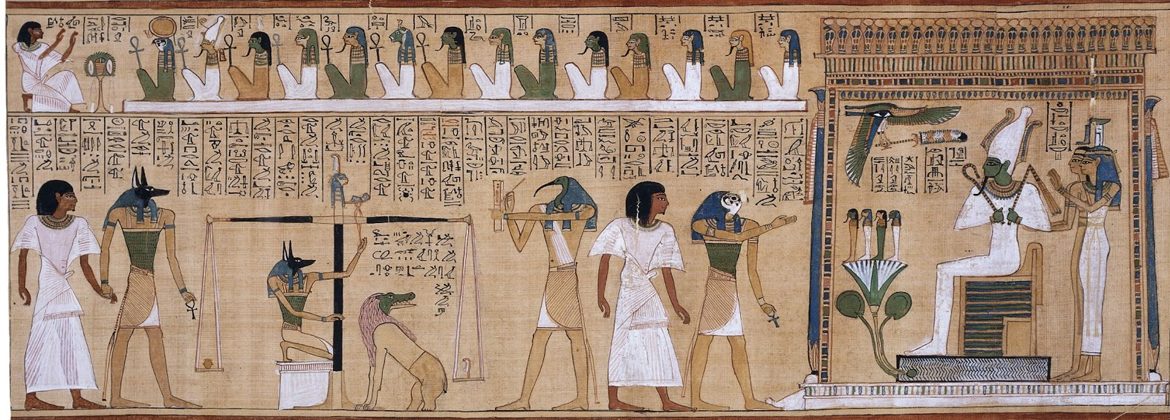

The Judgement of the Dead by Osiris

The Judgement of the Dead by Osiris

“A good name is better than precious ointment, and the day of death than the day of birth.”

(Ecclesiastes 7:1)

A sage spoke significant words more than three thousand years ago, when they were recorded, words that seem to defy common sense. How could we have a positive outlook on the day of death? What is the relationship between life and death? Moreover, what is it that determines the weight of a life?

Numerous ancient civilizations asked these questions; for many of them death was not the end but a passage to another level of existence, and each culture had their own story describing the actions and rituals that made this transition easier. Due to its strong symbolism and the influence it had on later civilizations, the Egyptian account of the Judgment of the Dead by Osiris may well be the myth that best portrays it.

Divine unity and harmony were central concepts in Ancient Egypt, and thus they influenced the life and death of people. The Neter or One was thought to be the source and matrix of everything, and it manifested itself through the Neteru, the gods personifying the fundamental aspects of unity. The figure of Maat, a symbol of truth, justice and cosmic harmony, was among them. She was depicted as a woman donning an ostrich feather on her head, and she was considered to be the daughter of the creator god Atum-Ra. Maat means “righteousness”, and it is the abstract concept of good, balance and universal justice that have prevailed in the world from its origin and from which man should not distance himself; it stresses what is trustworthy, real, genuine, and unalterable. Therefore, her feather was the measure by which the conduct of the deceased was judged.

The Egyptians believed that every human being has a physical body and a “Ka”, the immaterial force that continues to live after the body perishes. After this, the spirit of a dead person would arrive in the Duat, or the underworld, which was presided over by Anubis, a jackal-headed or dog-headed deity. Similarly, the ancient Mayans and Aztecs believed that a dog guided the souls of the dead through the Mictlán, the underworld. Once in the Duat, the deceased faced a court at the head of which was Osiris, the green or black-skinned god of the afterlife. The green color of his skin is a symbol of vegetation and regeneration, a symbolism that the Druids would take up later, and that was personified by their “green man”, the god of fertility and nature. Likewise, several elements of the Osiris myth bear similarity to prominent passages from the life of Jesus for Christians. Thot, the god of wisdom, completed the court. Also known as Hermes and Mercury in other times and cultures, he served as a scribe in the trial.

The heart was the center of life for the Egyptians. Learning, understanding, and reasoning resided in the heart. And the heart accompanied the deceased on the journey to the afterlife, it was the only viscera that remained within the mummified body. During the trial, the Ib (the heart) was placed on one side of a scale balanced against the feather of Maat on the other side. The deceased would then recite the “Negative Confession”, a list of 42 sins which they swore they had never committed. An intense scene, its moral significance is similar to that later found in the “Ten Commandments” as presented by Moses whose history and that of the Hebrew people are closely linked to Egypt and its mysteries. If the Ib was found to be lighter than the feather, the deceased obtained a favorable sentence which assured them eternal life. If, on the other hand, it was heavier than the feather, which implied impurity, they were thrown to Ammit, who was depicted as a crocodile-headed, hippopotamus-legged, and lion-bodied being who would devour them.

The judgment of the Dead by Osiris as immortalized by the Papyrus of Hunefer, together with the Papyrus of Ani, are classic examples of the Book of the Dead, a funerary text dating from Ancient Egypt that brought together the formulas and spells destined to help the deceased to overcome the Judgment of Osiris.

The Egyptians and other ancient civilizations believed that the disappearance of the physical body meant neither the end of life nor a loss. Taking advantage of the passage through the physical world, and having a virtuous and honorable conduct which allowed each being to transcend the forms and to return to its intrinsic nature was what mattered to them. The role assigned to actions by this story, and their moral value, could be linked to a reflection made by a Western thinker several centuries later: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”

The spectacle of the cosmos and the multitude of worlds that inhabit it moved him deeply, as did the ability of man to be free by manifesting independent behavior. As Góngora, the great baroque poet put it: “Born but yesterday, to die next dawn.” Mortal, fleeting, small before the immensity of the universe, where do we find our significance, our dignity, that which places us beyond our own death? The Egyptians believed the answer was in our behavior: our actions define us, and they echo in eternity. Perhaps the words of that sage will take on a whole new meaning now. Maybe that way the day of death means not the end but a beginning.