The Peabiru Trail

The Peabiru Trail

The Tupi-Guarani say that, in time immemorial, they lived in a magnificent place where peace reigned, ‘arrows hunted alone’, where there was no evil, no sadness, no death and everyone was happy. It was the Land Without Evil. One day, however, the men who lived there disrespected the rules and were expelled.

The Tupi Guarani originated in the central Amazon region and, around the fourth century BCE, they began an epic migratory journey. A part of these indigenous people went towards the south and east of the continent, giving rise to many Guarani ethnicities such as the ñandevas, kaiowás and the mbyás (in the central-west, southeast and southern regions of Brazil) and many others with Tupi ancestry such as the tamoios, carijós, goitacazes and the aimorés on the Atlantic coast of the southeast region.

The Tupi Guarani originated in the central Amazon region and, around the fourth century BCE, they began an epic migratory journey. A part of these indigenous people went towards the south and east of the continent, giving rise to many Guarani ethnicities such as the ñandevas, kaiowás and the mbyás (in the central-west, southeast and southern regions of Brazil) and many others with Tupi ancestry such as the tamoios, carijós, goitacazes and the aimorés on the Atlantic coast of the southeast region.

When the Europeans landed here, these ethnicities were in a process of booming territorial expansion, despite the conflicts among them.

We may list many reasons for this migration, but there is a fundamental one that was at the center of the Tupi-Guarani collective imaginary: to find the Land Without Evil from which they had been expelled one day.

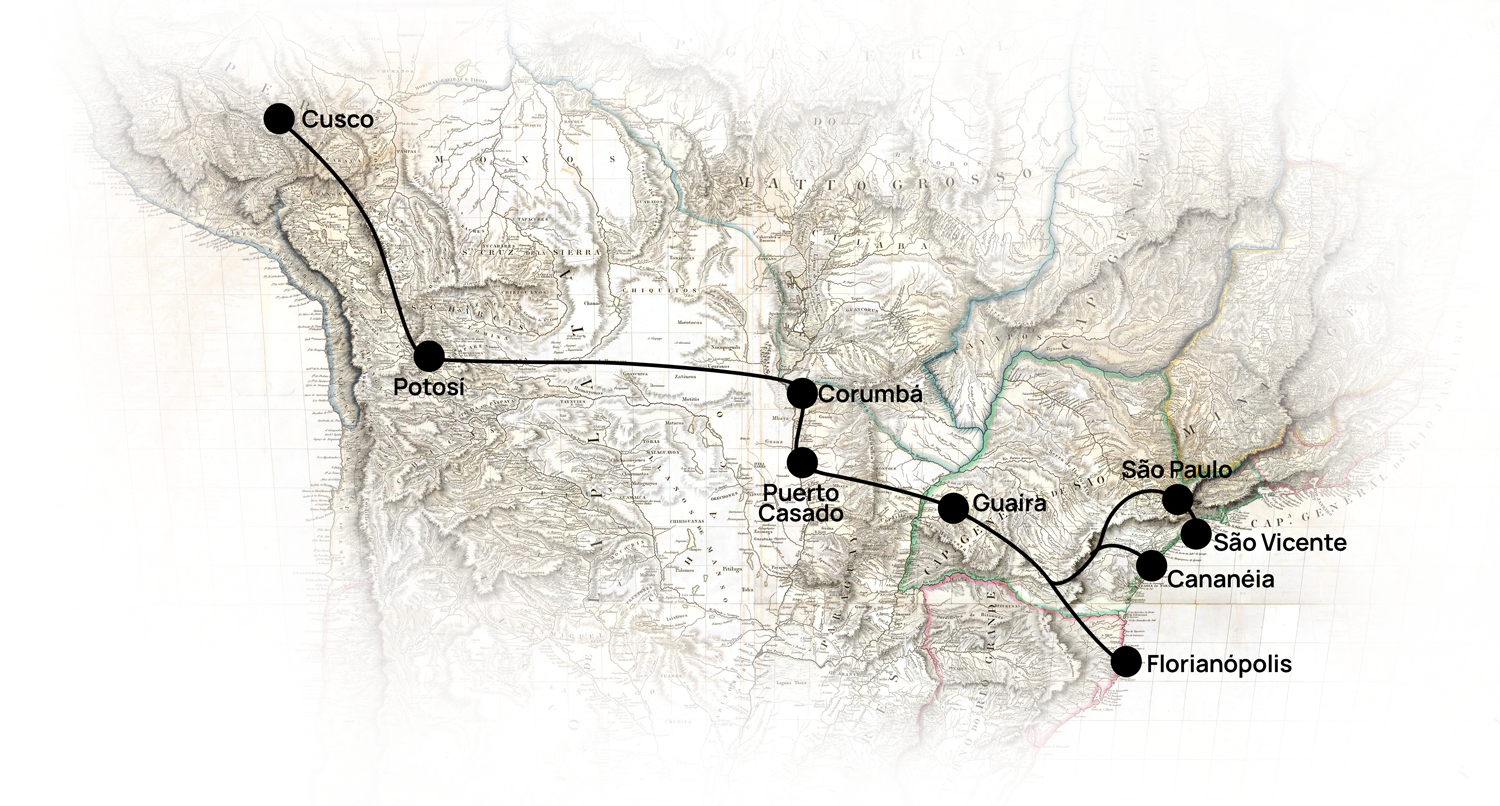

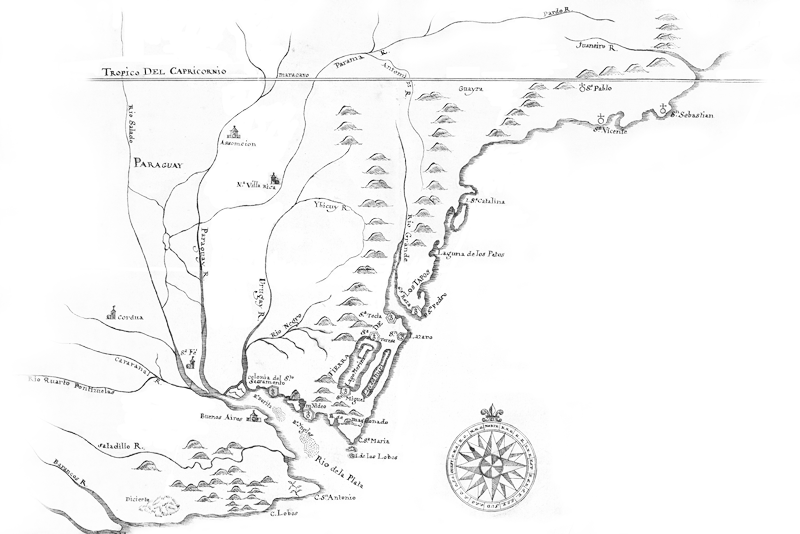

And in order to get there they would have built a trail, a kind of spiritual route that began at the city of São Vicente, cutting through the states of São Paulo and Paraná in Brazil, going towards Asunción in Paraguay. From there this road connected to the road network of the Inca empire, going up the Andes Mountains to its capital, Cusco, currently Peru, and then to the Pacific Ocean. It was the Peabiru Trail.

Trail of the Sun (from east to west), back and forth, beaten trail or crushed trail, trail to Peru, there is no definite translation for its name. The fact is that Peabiru became one of the most important transcontinental routes of the entire pre-Columbian America, as it connected a myriad of peoples and villages, allowing the circulation of people, cultural and merchandise exchanges. Its origin, however, is connected to a mystical, sacred search as it would, somehow, allow the connection with the world of opulence, freedom and immortality.

It was still in the beginning of the XVI century that Europeans began to hear the indigenous people tell stories about Peabiru, slowly and in a very diffuse way (the trail was part of their deepest beliefs and was, therefore, a secret).

Those tales were not very encouraging, however, as they also mentioned it was a trail that crossed the territory of many indigenous ethnicities who would do anything to prevent foreigners from passing through their lands.

Peabiru really attracted the attention of the Portuguese and the Spanish as they disputed the land below the Tropic of Capricorn for a long time. The settlers found out that there were two ways to access the center of South America: by navigating the Río de la Plata, Paraguay and Paraná rivers, or through Peabiru. Controlling these routes was strategic to reach the Inca Empire and its legendary mountain of silver, Potosí.

Meanwhile, the Jesuits approached the Indians in an attempt to catechize them. Their strategy was to get to know the indigenous cultures in order to convert them. And that’s how they came to know about an important character for the history of Peabiru.

Sumé, Zumé, Pay Sumé, Tumé… these are some of the names of the mythical character who, according to legend, came from the sea with his gray beard and gray hair, fair skin and wearing a tunic. Sumé taught the Tupis agriculture, established rules for life in society and would have opened the Peabiru Trail, among other feats. In the Missionary Fathers’ view, such characteristics made him rather similar to a very important character in Christianity, Saint Thomas, the “Apostle of India”, who would have come to the Americas with the goal of evangelizing, many centuries before the European conquerors. That was the belief of priests Manuel da Nóbrega and Antônio Vieira, for example. All conditions found among indigenous people led the missionairies to believe that it would be possible to catechize them by trying to merge the figures of St. Thomas and Sumé. So much so that the clergymen began to call Peabiru “The trail of St. Thomas.

In this context, we may add the myth of the Land Without Evil to the belief spread throughout Western Europe that the biblical Eden existed physically somewhere in the Atlantic. The description of the wonders found in America by European explorers fomented the collective imaginary of this people: had Paradise been found? Was there a sacred trail to reach it? During those early days of European conquest there was a mix of expectations for riches, possessions and spiritual salvation.

With the passing of time, the extinction of indigenous ethnic groups, and the advance of agriculture, cities, and roads, the Peabiru Trail eventually disappeared and many began to doubt its existence. It almost became a legend. A few decades ago, however, it was proved that it actually existed.

This is a brief history of the road that was much more than a means of connecting regions, becoming a symbol of the search for an ideal place and collaborating with the cultural syncretism of European and indigenous elements, and, definitively, contributing to the formation of one of the most striking characteristics of the Brazilian imagination: the belief in a better future.

Bibliography:

CHAUÍ, Marilena. O mito fundador do Brasil. Folha de São Paulo, March 26, 2000. Available at https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/mais/fs2603200003.htm

HOLLANDA, Sérgio Buarque de. Visão do Paraíso. São Paulo, Brasiliense Publifolha, 1994. Available in PDF https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/5502207/mod_resource/content/1/HOLANDA%2C%20S%C3%A9rgio%20Buarque%

20de.%20Vis%C3%A3o%20do%20Para%C3%ADso.pdf

NAVARRO, Eduardo de Almeida. Terra sem Mal, o paraíso tupi-guarani. Available at https://tupi.fflch.usp.br/sites/tupi.fflch.usp.br/files/NAVARRO,%20E.A.%20A%20terra%20sem%20mal,%20o%20par%C3%

A1iso%20tupi%20guarani..pdf

CAVALCANTE, Thiago Leandro Vieira. Apropriações e Influências do Mito do Pay Sumé na Evangelização feita pelos Jesuítas na América do Sul nos séculos XVI e XVII. Available at https://anpuh.org.br/uploads/anais-simposios/pdf/2019-01/1548206573_0b31c8a34a2a7856ddb71bda68a038a4.pdf

NEVES, Walter, BERNARDO, Danilo V., OKUMURA, Mercedes, ALMEIDA, Tatiana F. de, STRAUSS, André M. Origem e dispersão dos tupis-guaranis: o que diz a morfologia craniana? Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 2006. Available at https://www.scielo.br/j/bgoeldi/a/nfVcBnD7zpgwzfznddh4S3r/?lang=pt&format=html#

Caminho do Peabiru, de Lá para Cá. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7SojNJmu4NM

http://wibajucm.blogspot.com/2011/05/peaberu-o-sagrado-caminho-de-sao-thome.html